All my life I have maintained that the people of the world can learn to live in peace together if they are not brought up with prejudice. (Josephine Baker)

My blogs have always included either facts or poetry with one exception. Once I wrote a flash fiction piece, The Inside of a Ping Pong Ball, published in 1995. While looking for another document, I discovered a short story I had published in Dream Weaver, a local magazine that unfortunately is no longer operating. This fictional piece is longer than my usual entries. However, I think it fits as well today as it did in any century.

BETWEEN CHESTER AND ME

Mom and her friends said Chester’s dad was nuts for sending him to an expensive private school after he failed third grade in public school. Again. Especially since the money he spent on out-of-parish tuition could have replaced that worthless pickup truck he drove. But I pretended I didn’t hear. Mom didn’t care what I thought anyway. She said that I may be eight years old, but I could give out eighty years’ worth of opinions. Seems to me I wasn’t allowed to have one different notion about anything, much less too many.

“We get nasty notes about how much money we owe,” Chester told me, his mouth so full of crooked teeth, even I stared, and I was his best friend. “But Dad always pays. Late maybe. Just has to borrow a little once in a while.”

“So, doesn’t change a single game we play,” I said. “Uhm. You can’t come over today. I’ve got a doctor’s appointment, just for a check-up. See you at school tomorrow.”

I ran off before Chester saw the lie in me. I wish he wouldn’t tell me about his money problems. His dad’s dark shaggy beard and one pair of paint-spattered jeans told me he didn’t have much. Unless he owned more than the one pair of pants I saw, with a star-shaped tear in the knee and copper flecks of something on the seat. Chester wore old clothes like the ones we gave to the Salvation Army, things that were too shabby to wear, but too good for rags. Mom said I should never say anything mean to him. But I shouldn’t bring him home either.

“Stacey, Chester’s not all there. Do you know what I mean?” she said.

“Not all where?” I lifted the lid to the sugar jar and tapped the sides a few times. I thought about sucking on one of the crystal chunks that fell into the center, but I didn’t really want it. Besides, it would fall apart as soon as I picked it up. Just like most of my arguments with my mother.

“Don’t pretend ignorance,” Mom said. “You never know what someone like that is going to do. Besides, it wouldn’t hurt for you to play with another girl now and then.”

I knew better than to argue anymore. I always ended up with extra chores if I did. But Mom didn’t understand. The other girls wanted to be fashion designers or actresses. Or they played with dolls in boring lace dresses and talked for them in voices that sounded like they’d been sucking-in helium balloons. I never understood how someone could prefer fancy pretend to football. Of course, some of the boys would think since they were boys, they had to be boss. I hated that. Chester never played by those rules.

Once I broke a string on a brand-new gold yo-yo. I tried to tie the broken part back on, but I knew that wouldn’t work. I was just being stubborn and trying to prove a point about how I lost good birthday money on a piece of junk. So, I got mad and hurled the worthless thing at a fat, old tree. Chester grabbed the two broken halves and covered his ears with them.

“Hey, Stacey? Look, my head’s winding the string.” He squatted down and stood up again until he got dizzy. Then he stuck his tongue out at me and I laughed so hard I forgot to be in a bad mood.

In class, Chester would suck in air through his teeth and fold his arithmetic papers like an accordion. Sometimes his answers were so wrong the other kids laughed their heads off. Then it would take Mrs. Craftwood at least five minutes to quiet everybody down. But I wouldn’t laugh, even if Chester said something really funny, like the time he asked if the earth was hollow like the globe in the science room.

“Yeah, hollow like his head,” Jerry Freeman whispered. Then he stared at me. “Are you going to marry Hollow Head?” Every freckle on Jerry’s face flashed malice.

I tripped him when he went to sharpen his pencil. He bruised his elbow when he fell into another kid’s desk. I claimed it was an accident, but I know I didn’t look the least bit sorry. Mrs. Craftwood sent me to spend the afternoon in the principal’s office, and I had to sweep floors after school, but it was worth it.

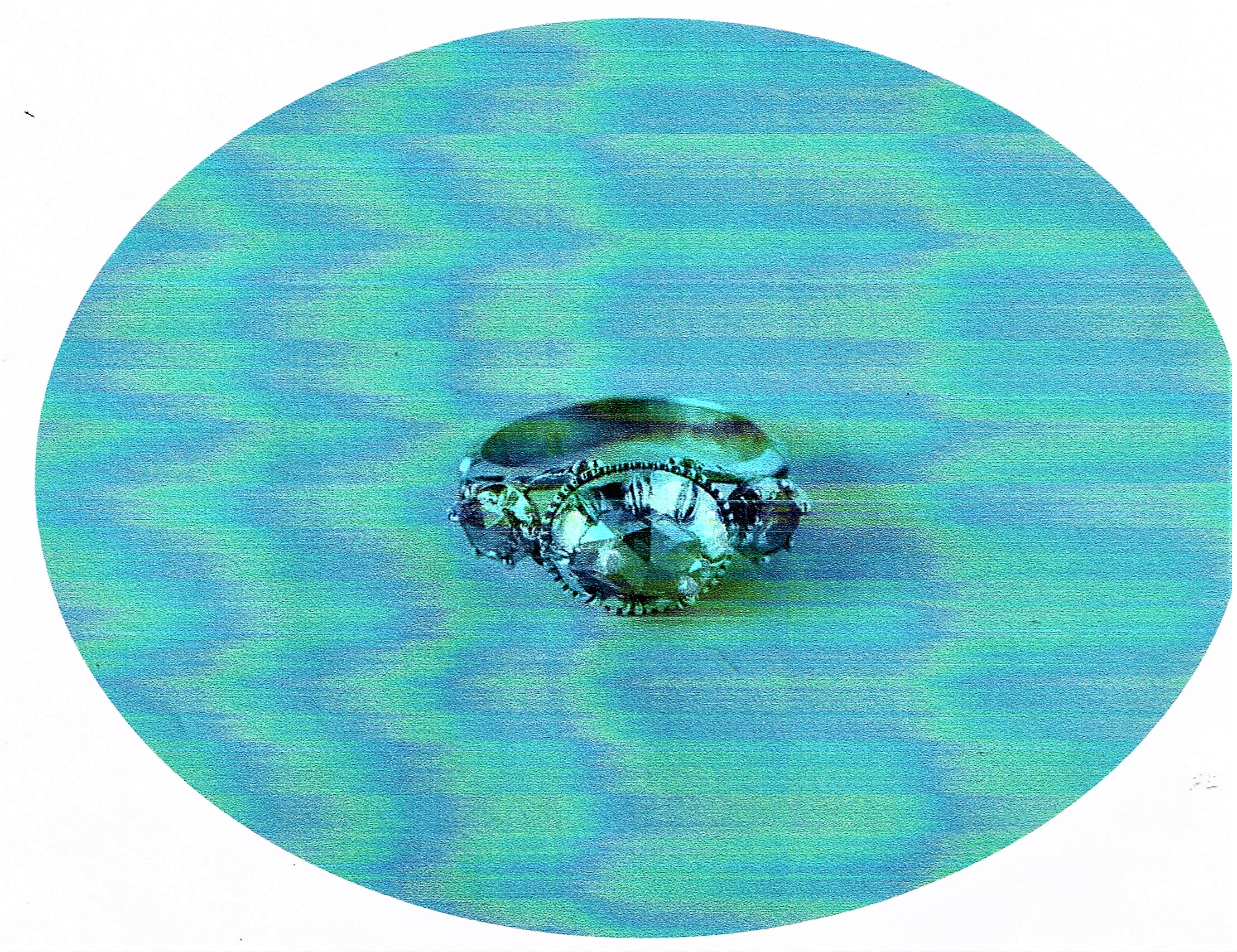

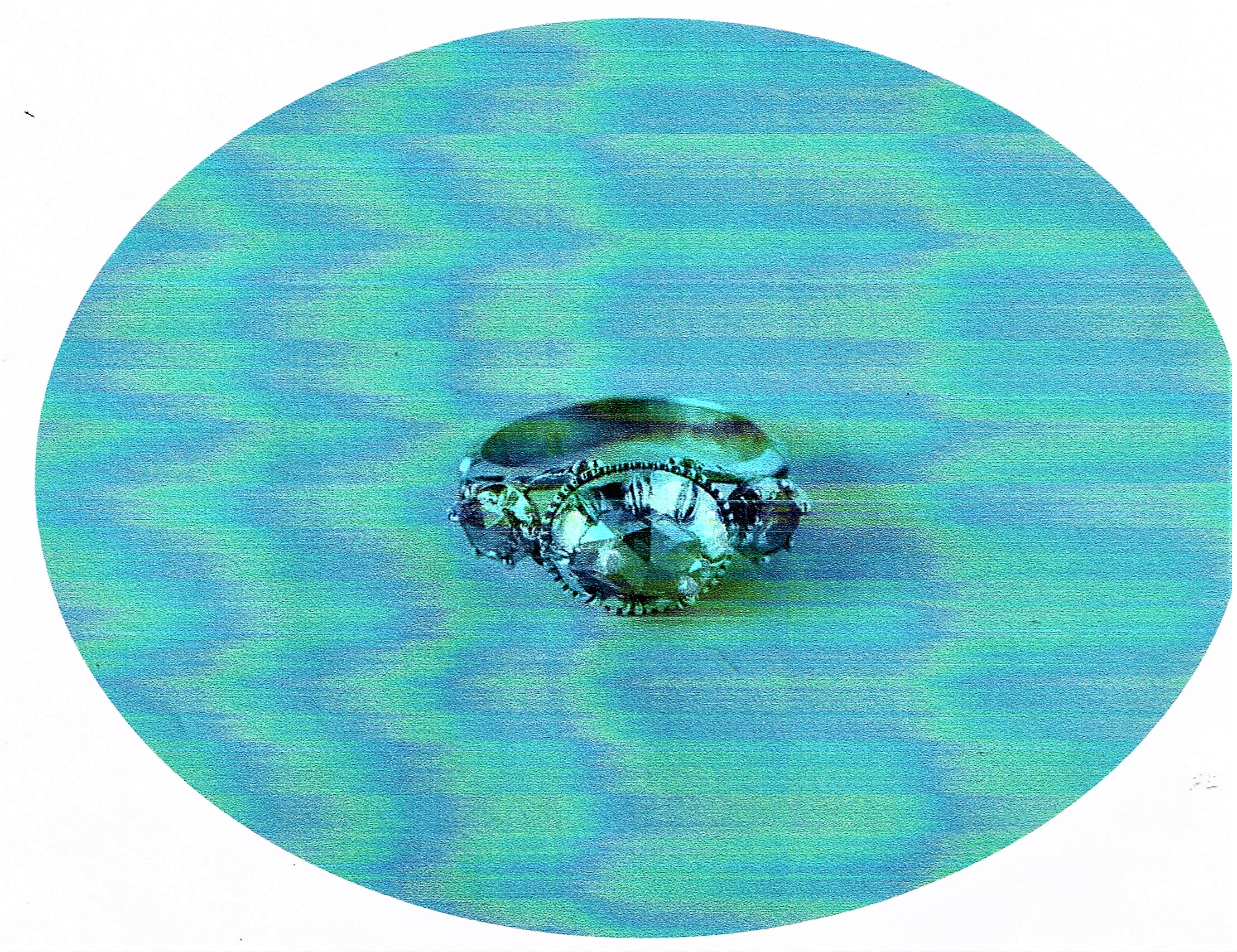

Chester kept a tiny, gray velvet box hidden in his pocket. A ring with a big white diamond lay in a soft spongy space inside. He said it belonged to his mom. She died and went to heaven not long after he was born.

“You can’t touch it, Stacey,” he said. “Only I can do that ‘cause it belonged to my mom. I like to hold it and pretend she’s right next to me. Dad said she had hair dark as molasses and a voice that made the angels cry.”

He rolled the ring in his palm, then held the jewel to the sun, as if he could see more than a few sparkly places. Then he carefully put the ring back inside, and we ran to find swings next to one another on the playground. If there weren’t any, we climbed the monkey bars and he never seemed to care that I always beat him to the top.

One day in the lunchroom, Mrs. Craftwood saw Chester take the ring out of his pocket. She dragged him to the principal’s office. I threw away the other half of my bologna sandwich and followed them. They didn’t close the door. I saw everything.

“This ring had to be stolen,” Mrs. Craftwood told Mrs. Austin, “Because this boy’s father is entirely incapable of affording something like this.”

Mrs. Austin glared at Chester. “Stealing is a sin, son. You should know that.”

After school when Chester’s dad got to the principal’s office I sat outside the office and listened again. I knew that he had a job in a big, important office a long time ago, but the company closed one day, and he never found another job like it. Then after his wife died, he moved into an old four-room house on the edge of town and did odd jobs now and then. Folks said he didn’t seem to care anymore. But when he charged into Mrs. Austin’s office, it was clear he cared about something.

He didn’t say anything while she and Mrs. Craftwood accused Chester of stealing. Then he asked if either one of them took a close look at the ring.

“Why should that be necessary?” Mrs. Austin asked.

“Because it doesn’t take much light to see the truth in that diamond. Let me guess. Came in a gray box. Smells a little like grass stains and peanut butter.”

“What are you talking about, sir?” Mrs. Austin said.

I had to cover my ears because Chester’s dad got so loud. And this time the door was shut. He’d slammed it when he went inside. Hard.

“Would a real diamond look as scratched up as the side of a matchbox?”

“Please lower your voice,” Mrs. Craftwood said.

“Not until you return his mother’s ring.”

I wanted to lean into the door and catch everything that went on, but then Chester’s dad started talking about how his wife deserved better, and so does Chester. Wasn’t so exciting anymore. Something I couldn’t explain made me feel strange, almost like I walked into the boys’ dressing room by mistake. So, I sat on the bench outside the door and waited for what seemed like a long time.

“Thank you,” Chester said as his dad opened the door. Simple, like nothing was ever taken from him in the first place. He didn’t even see me right away because he was too busy slipping the ring on and off of his finger.

But his dad’s face looked so red it must have hurt. I could have sworn it burned right through his whiskers. He stopped when he saw me. “Stacey, you’re a good kid. Chester’s crazy about you. Don’t ever get too big for yourself.”

“I won’t,” I said. But I thought that was a strange thing to say.

Chester never did come back. He went away to a special-needs school on the other side of town. Mom said it was time for me to start playing with normal children.

“What’s normal?” I asked, and Mom accused me of being smart aleck.

But this time I wasn’t.

After that, I decided it was best to be vague about what I was doing. Sometimes I went to Chester’s house, and we explored the woods behind it. We hoisted ourselves into the trees with lower branches and hunted for birds’ nests and woodpecker holes. He carved our names into a young beech tree.

“Someday when we’re old enough, let’s get married,” he said. “We’ll come back here, and I’ll draw the heart and put the date on it.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But let’s look for salamanders down by the creek now.”

“Okay. But why can’t we ever go to your house to play?”

“Mom said I had to play outside. She’s cleaning.”

“You said she was sick last time,” he said.

“That’s because all she does is clean. And that much cleaning would make anyone sick.”

I stopped going to his house as much because I got tired of lying. To Mom. To Chester. Then one day I told Mom I was going for a long bike ride all by myself. I went to Chester’s house, but no one was there. When I peeked into his house it was empty, blind-dark. On the way home I felt mean like somehow, I made Chester move away. I stopped at our beech tree in the woods, took a sharp rock, and etched a shallow, lopsided heart around our names. It didn’t look very good. I’m not sure why I did it. Playing house never appealed to me. And Chester and I were never boyfriend and girlfriend.

But when I went to my cousin Janet’s wedding that summer, I thought about what it would be like to be a grown-up getting married. Maybe just for that day, I would be willing to wear a lace dress, one made by a silly third-grade girl who grew up to be a fashion designer. Of course, I didn’t want to marry just anybody. The groom needed to be special, someone like Chester, who could give me a fake diamond, yet be real inside.

Read Full Post »